Scrap Gardening for Beginners

Scrap gardening is great for beginners who are wanting to experiment with their first garden and for those who just do not have room for a large garden in their yard. It is also a great way to save money on fresh food!

By Savannah Kohler, Leadership in Urban Agriculture Internship, 2020

An estimated 1/3 of all food that was made for consumption, ends up as waste instead. (1) Along with composting, scrap gardening is one of many strategies used world-wide to help with the reduction of food waste. While eating a higher quality diet is related to less cropland waste, it does have a negative association with food waste. (2) By taking the time to turn some of our kitchen scraps into a small scrap garden, we are doing our part in helping to provide a sustainable food system.

Scrap gardening is great for beginners who are wanting to experiment with their first garden and for those who just do not have room for a large garden in their yard. It is also a great way to save money on fresh food!

How is this done?

While each plant may vary in the amount of water used, the length cut of the scraps, and the amount of time it takes to regrow, it is all still remarkably easy and very much achievable! To begin, you will need for your plants to grow roots. See below for instructions.

What plants can I regrow?

You can regrow most of your veggies and fruits, but not all. Here are some examples of popular options that you can regrow and how to do it.

GREEN ONIONS: Cut off the top of the plant and keep the end that grows roots. Plant it in potting soil and place it in a well-lit room. Soon, the green onions will begin to grow back, and you can snip them off the plant and use them as needed.

CELERY: Cut the stalk, leaving about two inches at the bottom. Place the two-inch-long end in a bowl of very shallow water. When leaves begin to grow on top, you can move into potting soil and watch it grow.

ROMAINE LETTUCE: Cut the lettuce, leaving about two inches at the bottom. Place the two-inch-long end in a shallow bowl of water. As leaves grow, you may eat them.

POTATOES: Wait until your potato is starting to sprout. When it does, cut the potato in slices around the sprouts. Plant in deep soil with the eye facing up. Cover the potato entirely with soil.

HERBS: Pick most leaves from the stem, while leaving the only top few remaining. Place the stems in a glass of water. Replace the water every few days. Plant stems in soil once they have grown their roots.

Helpful Links:

https://www.diyncrafts.com/4732/repurpose/25-foods-can-re-grow-kitchen-scraps

References

Anastasia M, Alexandru J, Liliana S(C. Studies on the use of vegetable scraps. https://ibn.idsi.md/ro/vizualizare_articol/72422. Published February 20, 2019. Accessed July 27, 2020.

Conrad Z, Niles MT, Neher DA, Roy ED, Tichenor NE, Jahns L. Relationship between food waste, diet quality, and environmental sustainability. Plos One. 2018;13(4). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0195405

Brassica Pests: Solutions (Part 2 of 2)

Once you have identified which pest is attacking your brassica crops, then you can work towards managing the problem. In this case, most of the treatments are very similar for all 3 kinds of caterpillars.

By Rebecca Halcomb, Leadership in Urban Agriculture Internship, Fall II 2020

Once you have identified which pest is attacking your brassica crops, then you can work towards managing the problem. In this case, most of the treatments are very similar for all 3 kinds of caterpillars. There are a few specific solutions, but I’ll note those below:

Row Covers: Cover brassica crops with floating row cover or screen cover from when you plant to when you harvest to keep the butterflies and moths off. You should still regularly inspect though. You can also use pantyhose on cabbage heads, and those will grow with the plant and let enough air, sunlight, and moisture in.

Hand-picking: It can be time-consuming and they can be easy to miss, especially the 2 green species. They like to hide on the underside of the leaves, and blend in with the leaf veins. It’s actually much easier to see their dark green frass (poop) than it is to see them. You can drown them in soapy water once you pick them off.

Use Predators: Hang birdhouses in or near the garden or let the chickens into the garden temporarily once the plants are hardy enough, and they will eat the caterpillars for you.

Plant Tolerant Varieties: Some examples of green cabbage varieties that are a more resistant are Green Winter, Savoy, and Savoy Chieftain. You can also try planting red-leafed varieties of cabbage and kohlrabi, which are less desirable because of lack of camouflage for the 2 green caterpillars.

Attract Beneficial Insects: You can either buy them directly, or plant a good selection of flowers and flowering herbs around your brassicas to attract the beneficial insects that will prey on your pests. Some plants to use for this would be parsley, dill, fennel, coriander, and sweet alyssum. (Be careful if cross-striped cabbageworms are your culprit, because they also destroy parsley.) These flowers will attract parasitic wasps, paper wasps, yellow jackets, and shield bugs. Parasitic wasps will lay their white cocoons on the caterpillars’ backs. Leave the cocoons alone to kill off your pest, and then you’ll have a new generation of parasitic wasps for later waves of pests. If you don’t want to rely on your flowers to attract them, you can purchase trichogramma wasps, and release them to destroy the pests’ eggs.

Use Companion Planting: Interplant companion plants among your brassicas that repel the butterflies/moths, like aromatic herbs such as lemon balm, sage, oregano, borage, hyssop, dill, and rosemary, or high blossom flowers like tall marigolds or calendula.

Use Trap Crops: For Loopers, plant celery or amaranth. For Cabbage Worms, plant nasturtiums or mustard. The butterflies/moths will lay their eggs on those crops first, and then once you see the pests, you can dispose of the trap crop to get rid of them.

Frequent Harvesting: For the cut and come again crops, such as Kale and Collard Greens, harvest the leaves more frequently to interrupt the pest life cycle.

Pheromones: Use pheromone traps to monitor and control their populations.

Biological Pesticides: Spray with BT (Bacillus thuringiensis). It’s a natural bacterium that kills caterpillars and worms. BTK sprays in particular do not harm honey bees or birds and are safe to use around pets and children. One source said to spray for Loopers early in the season as a preventative, and then use again for later waves. For cabbage worms, it said to spray every 2 weeks until they get under control. Another source said that one treatment in late summer approximately 2 weeks before harvest can greatly improve your crop quality. You’ll have to reapply after rain though.

Diatomaceous Earth (DE): DE is a very fine powder that when sprinkled can cut up any soft-bodied insect that comes into contact with it. This also has to be reapplied after rain.

Insecticidal Soap: Spray with Organic Insecticidal soap, but this also has to be reapplied after the rain.

Other Repellent Sprays: For Loopers, you can spray the crops with liquefied and strained cabbage loopers or hot pepper spray.

Seasonal Clean Up: For the cabbage worms, do a thorough fall clean-up of old plants and debris, since the butterflies like to overwinter there. (The white cabbage butterfly usually shows up early in the spring because they overwinter instead of migrate.)

Use Decoys: This method is a little experimental, but supposedly the Cabbage Butterflies are territorial and don’t like to lay their eggs if they think another female has already claimed your plants. So you can make white butterfly-shaped decoys out of plastic or another durable material, and put them by your garden plants. Make them 2 inches wide, and with 2 black spots on the upper wing. I think I’m going to repurpose some milk cartons and give it a try. Here’s the link to a template: http://goodseedco.net/blog/posts/cabbage-butterfly-decoy

RESOURCES

This was a very beneficial website that gave some practical tips on controlling cabbage loopers: https://www.planetnatural.com/pest-problem-solver/garden-pests/cabbage-looper-control/

Missouri Botanical Garden has info and tips:

Imported cabbageworm: https://www.missouribotanicalgarden.org/gardens-gardening/your-garden/help-for-the-home-gardener/advice-tips-resources/pests-and-problems/insects/caterpillars/imported-cabbageworm.aspx

Other Sources:

https://savvygardening.com/guide-to-vegetable-garden-pests/

Indigenous Agricultural Practices

Learn about Indigenous agricultural practices and some facts about traditional native food.

By Shea Metzler Leadership in Urban Agriculture Internship, Fall I 2020

Click on the image for a PDF version of the guide.

Friend or Foe: What You Didn't Know About Weeds

Weeding is one of the most essential tasks in gardening, and the job is never done. These backyard “volunteers” always seem to find a way to thrive. Knowing your weeds can help you out. Some weeds are tricky to combat and can really hurt your plants, but others can be quite useful. Knowing these things can help lessen your load and maybe even bring a little something extra to your garden. This video will focus on a few different weeds and how they might affect your garden.

By Louise Haupert, Leadership in Urban Agriculture Internship, Fall I 2020

For the video transcript, click here.

Environmental Justice Initiatives in St. Louis

Find out more about environmental justice and food justice work happening in St. Louis!

A Beginner’s Guide to Comfrey & Echinacea for Gardening and Healing

By Shannon Haubrich, Leadership in Urban Agriculture Internship, Summer III 2020

COMFREY

(Symphytum officinale)

Native to Europe, western Asia

Perennial

Comfrey digs very deep roots which absorb and redistribute nutrients in soil, which makes it an incredible ‘chop and drop’ fertilizer. It shades surrounding plants, acting as a living mulch, and when chopped, the plant breaks down, adding the absorbed nutrients back into the soil. Comfrey attracts pollinators, too!

MEDICINAL USES

Encourages wound healing

Diminishes scarring

Relieves arthritis and general muscle/joint pain

Provides healing for digestive ulcers

Eyewash for irritated eyes

*Take caution and research before using topically on an open wound or ingesting! Comfrey may re-bind skin and tissue too quickly, or seal in existing infection. It is also argued that comfrey, when ingested, can be harmful to the liver. Many people ingest comfrey in small amounts, but do plenty of research and ingest only if you feel safe.

COMFREY OIL RECIPE

Harvest comfrey leaves and allow them to dry overnight or in a dehydrator. Fill a glass jar halfway with the leaves, then cover with good-quality oil (cold-processed olive and/or coconut oils work well). Cover tightly, and let sit 4-6 weeks, occasionally giving the jar a light swirl/stir. After 4-6 weeks, strain out the herbs, and use the oil for topical application of comfrey as needed.

ECHINACEA

(two common species are E. purpurea & E. angustifolia)

Native to North America

Perennial

Echinacea grows abundantly in Missouri! It attracts many pollinators like butterflies, predatory wasps, and pollinating flies, making it a great companion for certain vegetables like tomatoes and peppers. Echinacea is also known to attract the goldfinch, which is lovely to see and friendly to garden fertilization.

MEDICINAL USES

Healing for wounds, bites, and stings

Immune support (take with raw, organic garlic for a powerful kick to viral infections)

Strengthens and clears lymph nodes

Powerful against infections, internal or external (i.e. bladder, ear)

Can be used as a pain reliever (Echinacea’s numbing effect makes it useful for dental pain)

ECHINACEA TEA RECIPE

Harvest any leaves, flowers, or roots you’d like to use in your tea (or use dried, store-bought echinacea). Boil water, pour over echinacea, and let steep for 15 minutes. This long steep time allows the medicinal properties to be extracted, especially from the plant’s thick roots.

How to Make a Milk Crate Garden

Follow these simple steps to make your own milk crate garden!

Beginner's Guide to Permaculture and Home Gardening

Collectively realizing ecological and food justice can and will start small, especially through the bioregional practice of integrating permaculture principles into home gardening.

By Liz Burkemper, Leadership in Urban Agriculture Internship, Summer II 2020

Collectively realizing ecological and food justice can and will start small, especially through the bioregional practice of integrating permaculture principles into home gardening.

To live bioregionally means to live in place: we are cognizant and contemplative of the ecological needs of our places, whether terrestrially or communally. We nourish Earth instead of stripping it down, we grow and eat in awareness of the natural ecosystems and natively thriving plants, we grow with the Earth instead of against it, we abide with our community rather than separately from it.

Our home gardens are perfect grounds for beginning to do so toward listening to the Earth and nourishing our (and our community’s) body. Through the practice of permaculture, we might thoroughly enjoy the Earth’s fruits—grown in harmony rather than in opposition—and what we don’t enjoy, we give away to our neighbors and back to the soil.

Some tips on bringing permaculture to your backyard/home garden:

1. Grow your soil! Instead of tilling, feed your garden beds—layer with cardboard or leaves/grass clippings from your yard. Through permaculture, we learn that every part of the life cycle is useful, and that soil is living, so we must nourish it instead of snuffing out its natural vitality.

2. Grow perennials! Unlike annual-only plants, perennials—especially when planted polyculturally so as to balance the garden ecosystem—won’t zap the soil nutrients + don’t need to start from seed over and over again. Think kale, garlic, rhubarb, chives, asparagus, artichokes!

a. Don’t forget: “perennial” does not mean “no tending required”!

b. Since perennials grow differently than many crops favored by modern industrial agriculture, many of these plants have been lost to history or are rarely found in the grocery store. Don’t be afraid to try veggies you have never tasted before!

3. Mulch mulch mulch! Mulch is the ultimate soil protector—from dryness + erosion, of essential microorganisms and insects, of soil moisture. Here’s an easy guide to permaculture mulching in your garden.

a. Use organic materials from your own lawn: grass clippings, leaves, pine needles, fallen branches, twigs, bark, (sometimes) rocks...

b. ...or find local byproducts (which are often free): grain husks, sawdust, woodchips c. Make a layer that’s three inches thick, and do it again!

4. Build a creative (i.e. no-row) space! Gardening and farming through plowed rows resists the natural thriving of plants, even visually—planted rows mean empty rows between them. Instead, mix your tall + short plants, let vines grow upwards on corn stalks, and plant with curves so as to use your garden space wisely and ensure healthy microclimates for your plants.

a. Unconvinced of the rad benefits of row-less gardening? Check out this deep dive into the advantages for small-scale gardeners!

b. Used on the Urban Harvest STL farms, raised rows are another low-maintenance, no-till means of building up your garden.

5. Don’t waste! Permaculture thrives on a closed-loop system: all waste (output) is reintegrated as resources (input) so as to ensure the dynamism and energy efficiency of the growing system. This means harvesting seeds, using weeds to rebuild the soil, composting, and more.

These are just some beginner’s tips! At the heart of permaculture and bioregionalism is listening and paying attention to the land on which we live, instead of forcing our own thoughts and desires onto the land or into our communities. This listening can be practiced anywhere and everywhere.

For more diving and digging, check out Deep Green Permaculture’s guide to starting your own permaculture garden + Permaculture News’ guide to doing so small-space intensively.

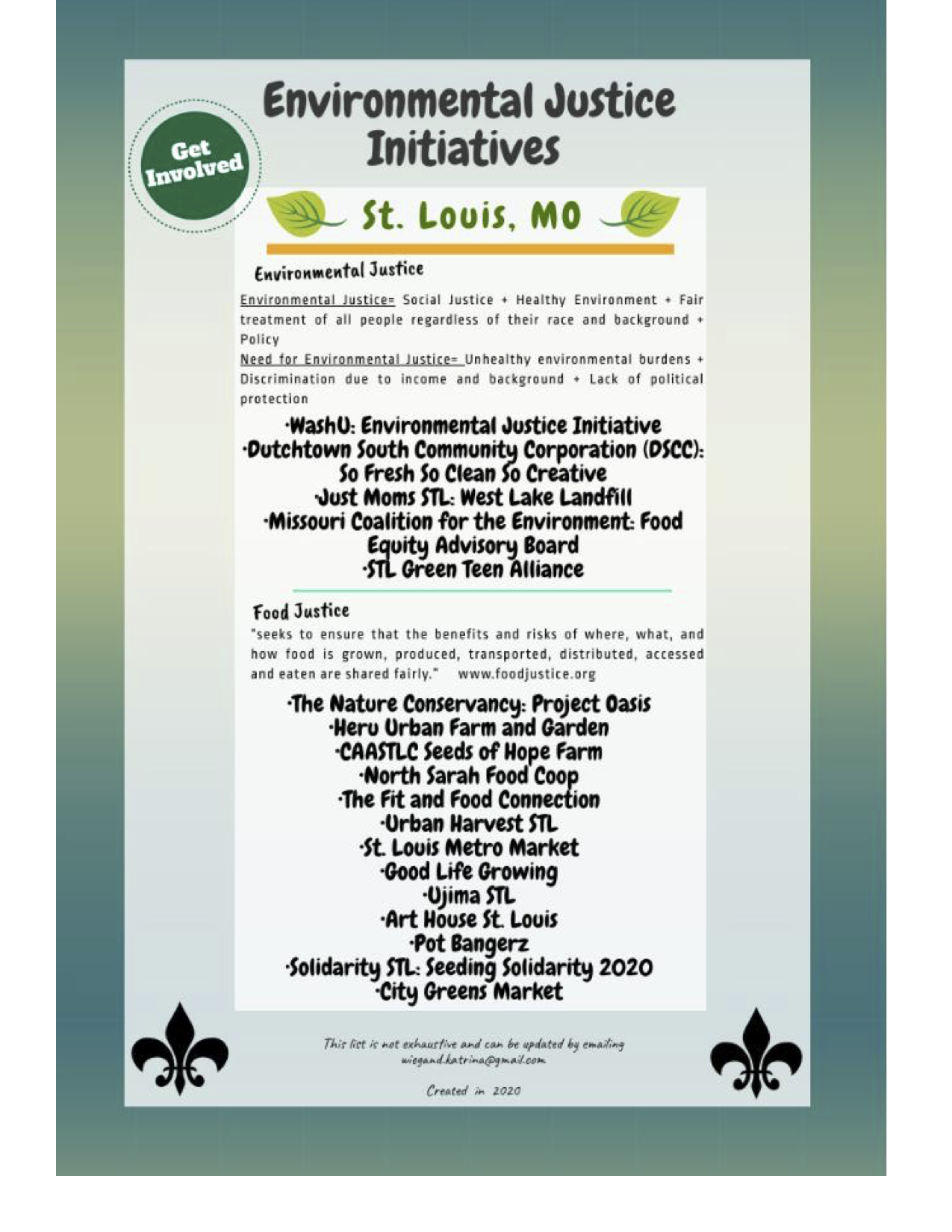

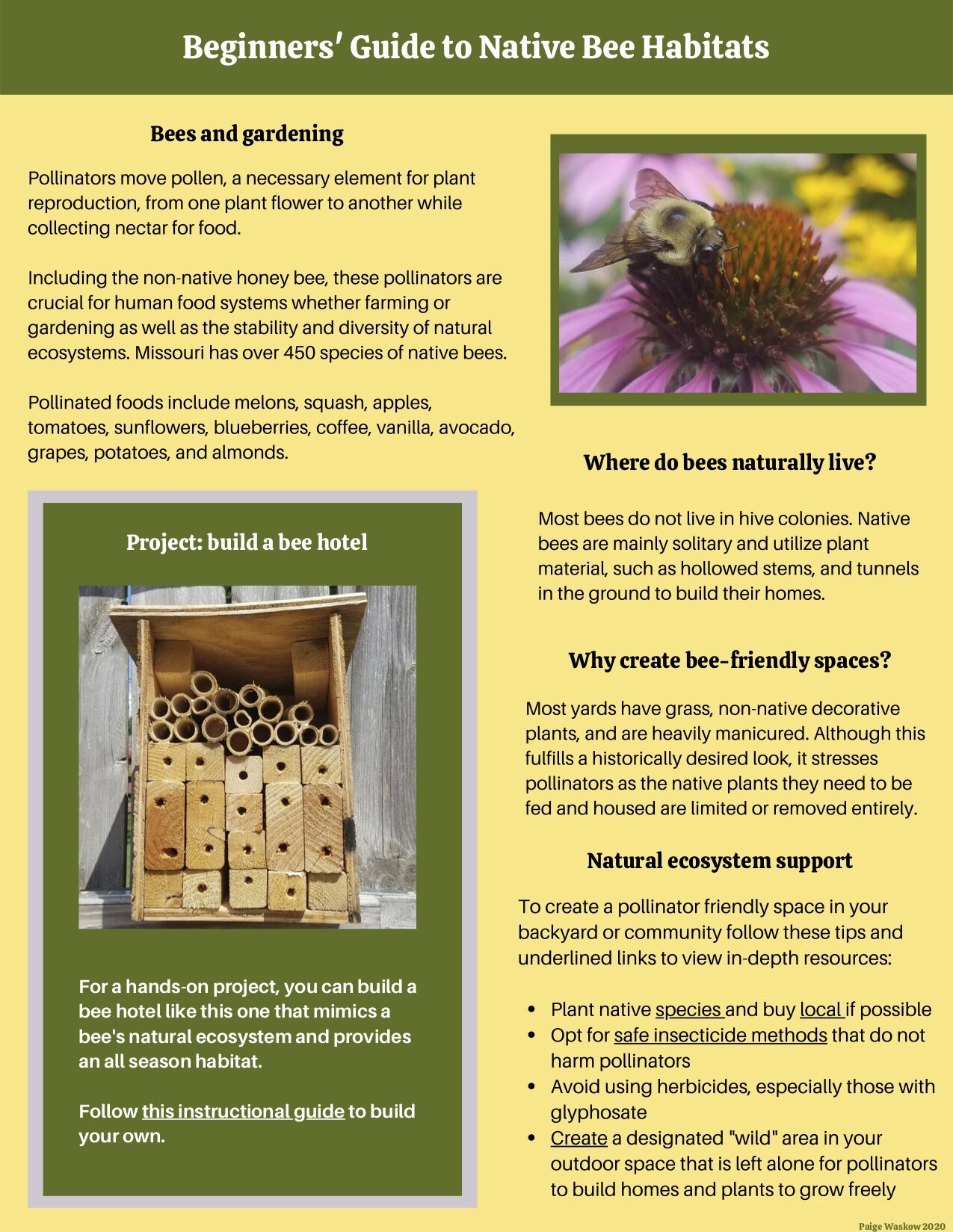

Beginner's Guide to Native Bee Habitats

Learn about the benefits of planting native flowers and some common examples!

Food Preservation Through a Culinary Justice Lens

Learn the basics of culinary justice, why it matters to urban growers, and some simple preservation methods to try yourself.

By Briana Robles, Leadership in Urban Agriculture Internship, Summer II 2020

Photo by Soul Fire Farm.

Introduction to Culinary Justice

Co-executive director of Soul Fire Farm and author of Farming While Black, Leah Penniman, eloquently stated that “our tables are healing tables, fellowship tables, and living history tables.” Likewise, our tables are also rooted in food apartheid, which presents itself in statistics such as “1 in 4 black children go to bed hungry” and the common illusion that “healthy cooking and food preservation is a ‘white people thing.’” Michael Twitty, Culinary Historian and author of The Cooking Gene, defines culinary justice as “the idea that oppressed peoples have the right to not only be recognized for their gastronomic contributions, but they have the right to their inherent value… to derive from them, uplift and empowerment.”

Why Culinary Justice Matters to urban growers

As gardeners, farmers, and foodies, we participate with the food system in inherently distinct ways. Growing, preserving, cooking, and feasting are ways of honoring generational wisdom and living sustainably for the sake of those who will come after us. Chef Kabui, a Kenyan chef committed to decolonizing our food, reminds us that “everyone has a farming history in growing and preparing food. So, find it. Connect with it- with that ancestor. Carry it on.” Growing food invites us to grow in awareness of our land, ourselves, and one another.

Basic Methods of Food Preservation

Farming While Black mentions various methods for cooking and preserving the food we grow including, preserving in soil and ash, Drying, Fermentation, In-Vinegar, Canning, and Freezing. Below, Fermentation and In-Vinegar food preservation techniques will be discussed, and example recipes will be provided. To learn more about other indigenous ways of preserving food from around the world, click here.

PRESERVATION BY FERMENTATION

Fermentation is a method of food preservation used throughout the world that increases the nutritional content of food with the help of bacteria.

Veggies that are great candidates for beginner lactic acid fermentation include:

Cabbage (below)

Turnips

Carrots

Cucumbers

Radishes

Green beans

Photo by Emet Vitale-Penniman for Farming While Black.

HOW TO MAKE FERMENTED CABBAGE

Recipe adapted from Farming While Black by Leah Penniman

Slice cabbage thinly

Combine with non-iodized sea salt at a ratio of 1-pound vegetable to 1-teaspoon salt.

Use your hands to massage the salt into the cabbage

Let it sit in brine while you sterilize the canning jars* in boiling water

*NOTE: Standard quart-sized canning jars holds about 2 pounds of vegetable

Pack brined cabbage tightly into jars pressing out air as you go, so that the cabbage fills the jar up to the bottom of the rim

Pour liquid brine over cabbage to completely fill jar

Place lid on loosely

Arrange jars on tray/pan/dish & place at room temperature* for 3 days

*NOTE: The hard-working bacteria will result in bubbling and loss of liquid

Top off each jar with brine solution of 1-teaspoon of salt per 4 cups of water

Secure lids on tightly & transfer to cool/ dark refrigerator or basement

Bonus: Recipe can be jazzed up using garlic, dill, mustard seeds, caraway seeds, juniper berries, & other spices.

PRESERVATION IN VINEGAR

In about 2030 B.C, vinegar was first documented for the preservation of cucumbers in Mesopotamia near the Tigris River. Below, is a recipe for Pikliz, a sour & spicy staple in creole cuisine and every Haitian household.

Photo by Andrew Scrivani for The New York Times.

HOW TO MAKE PIKLIZ

Recipe adapted from Farming While Black by Leah Penniman

Thinly chop cabbage, carrots, & onions

Pack into clean jar

Add distilled vinegar to just cover the mixture

Add spices: thyme, whole cloves, lime juice, salt, & hot peppers

Cover with lid and shake

Allow to sit at room temperature for 3 days before consuming

*NOTE: Always use a clean spoon every time you add Pikliz to your meal

Bonus: Experiment by adding other veggies including, cucumber, sweet peppers, turnips, cooked beets, green peas, fennel, radish, cauliflower, green beans, & boiled eggs.

Additional Resources you might be interested in…

To learn more about Karen Washington, who coined the term “food apartheid”, click here.

To watch a short video by Michael Twitty on Culinary Justice, click here.

To read an interview with Sioux Chef Oglala Lakota about decolonizing our diet, click here.

Works Cited

Andrew Scrivani. “Pikliz”. To view, https://cooking.nytimes.com/recipes/1017277-pikliz.

Ecks Ecks. "Cabbage". Licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/.

Penniman, Leah, and Karen Washington. Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm's Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land. Chelsea Green Publishing, 2018.

Twitty, Michael. “Gastronomy and the social justice reality of food”. YouTube, uploaded by TED Archives, 20, Dec. 2016. https://youtu.be/8MElzoJ2L6U.

Vitale-Penniman, Emet. The author grates cabbage on a mandolin as an initial step in fermentation. 2018. Photograph. Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm's Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land. Whit River City Junction, Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing, 2018. 239. Print.